Realist interviews with people with dementia

Written by attendees of the Realist Approaches in Dementia Evaluations and Reviews (RAID-ER) symposium at the University of Plymouth (November 2024)

In alphabetical order: Emma Broome, Lisa Burrows, Neil Chadborn, Sarah Griffiths, Anna Hockley, Gary Hodge, Aysegul H Kafadar, Pallavi Nair, Sue Molesworth, Tomasina M Oh, Andreia De Fonseca, Lorna Smith and Hannah Wheat

Blog writing coodinated by Dr Hannah Wheat

Background

Realist Evaluation is a theory driven approach to help us understand how and why an intervention works in a particular context under certain conditions. One method of obtaining data in such evaluations is realist interviewing.

Realist interviews have different aims to traditional qualitative interviews. Instead of trying to gain insights into individuals’ experiences and views of a specific subject, they seek an understanding of how certain programmes/interventions work, for whom and in what circumstances. To help achieve these types of insights, realist interviews are theory-driven and guided by existing theories on how programmes may work. Existing theories may have been developed through stakeholder engagement, literature reviews and/or previous research. Theories might take the form of a set of Context, Mechanism, Outcome (CMO) statements (or hypotheses) about how, why and in what circumstances the intervention will work/not work (See Box for key terms in realist methodology). Sometimes these are expressed as ‘If x, then y’ type statements.

Box: Key terms in realist methodology

Context – factors that influence how and when a resource (e.g. an intervention) is delivered and how mechanisms are triggered. For example: demographic characteristics such as age/gender, policies, attitudes and beliefs, geographical landscapes.

Mechanisms

Mechanism resource – the offering provided by an intervention or programme e.g. the support provided by an app, or a practitioner delivering a new form of support

Mechanism response – the change in reasoning (usually hidden or unobservable) in individuals that occurs because of intervention/programme delivery within a specific context, which leads to specific outcomes being realised. The type of mechanism-responses that may cause a programme/ intervention to work are multiple and are shaped by context.

Outcomes – effects of results produced by the mechanism within a particular context.

Examples of a C-M-O configured theory statement

If a dementia support worker provides people living with dementia, who are comfortable discussing finances, and are eligible for financial benefits (context), with tailored support that facilitates the application process (mechanism-resource), e.g. information on what support is provided, how to apply, and practical assistance with completing forms, then, due to enhanced motivation, people living with dementia will apply for financial benefits (mechanism-response). Financial support can help people living with dementia have a good quality of life (outcome).

During realist interviews, the interviewer will use questions that encourage a teacher-learner cycle to develop. This enables existing theories to be shared, corroborated, challenged, and refined with the aim of building understanding of hidden causal forces that routinely lead to specific outcomes. More details can be found here: https://www.ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_Realist_interviewing.pdf.

While there has been guidance on how to conduct realist interviews, insufficient attention has been given to whether and how the processes involved in realist interviewing may work (and can be supported) when interviewees have cognitive difficulties? As realist evaluations of dementia interventions become more common, it is important to recognise that realist interviews are a predominant means of collecting data for such evaluations. Therefore, guidance tailored to these situations is very much needed.

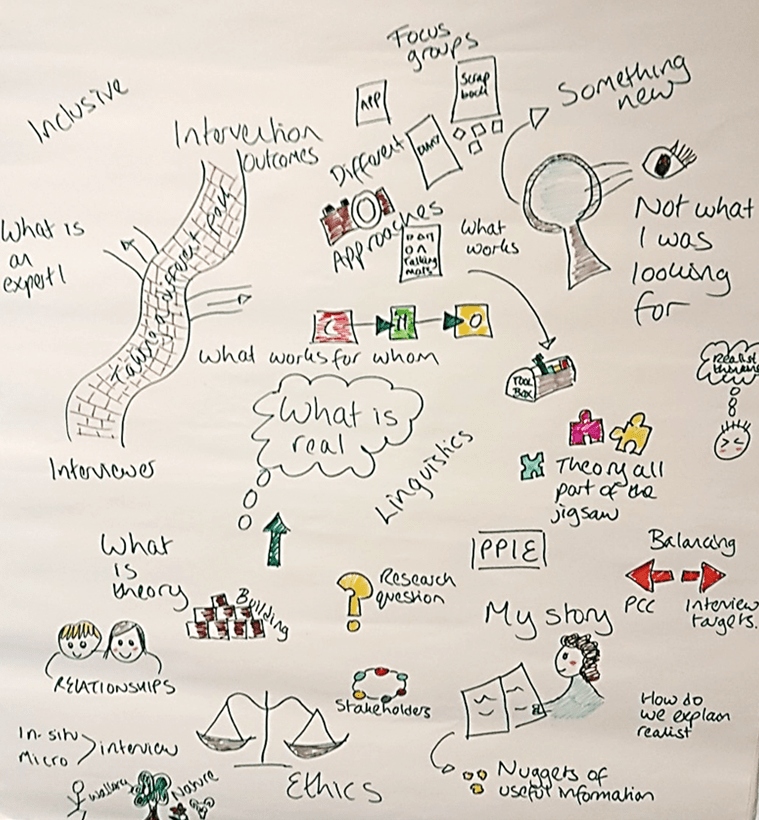

A group of dementia researchers (with an interest and experience in conducting realist interviews with people with dementia) recently met at a RAID-ER organised symposium, held at the University of Plymouth, to discuss this subject. Below are some key highlights from discussions and a visual illustration, created over the course of the day, that both informed and captured evolving ideas.

What are the potential challenges when conducting realist interviews with people with dementia?

- Working out how to adapt to the needs of people with dementia

It can be cognitively demanding to identify and recall how life changes occurred (i.e. the causal links that led to certain outcomes for a person ). Added to this, people with dementia may find it difficult to grasp abstract ideas and make sense of theories relating to interventions/programmes. We also know from experience that interviewees may (understandably) feel a strong desire to, or perceive there to be greater value in, sharing their life story (rather than thinking through and sharing the story of an intervention/programme). Collectively, these factors can sometimes make it challenging for the interviewer to re-direct people with dementia away from personal storytelling, toward an exploration of causal mechanisms of a particular phenomenon.

2. Uncertainties about the accuracy of interview data

All interviewees’ accounts are subjective, and influenced by biases such as time, personal beliefs, impressions of the interview etc. However, by asking questions that invite interviewees to consider what (hidden) causal forces may have led to change, collecting adequate data, and looking for patterns within the data, realist evaluators can work toward an understanding of how the intervention works, for whom, and in what circumstances.

Realist interview responses from people with dementia may sometimes be influenced by brain changes and/or perception disturbances. For example, people may experience hallucinations, time-shifting (orientation), delusions, and illusions. Such disturbances can potentially make it more challenging for researchers to discern whether their interview data is providing evidence about how the intervention/programme worked for them at the time of intervention delivery.

What practical approaches can support people with dementia to engage in realist interviews?

Before the interview

- Make sure you have sufficient time to do the interview, so people can still share their personal stories, but you can also introduce your theory-based questions when appropriate.

- Be flexible about when you do the interview so you can conduct it when people with dementia are less tired, when recall is better (e.g. just after an intervention event – although this can also be when people are most tired). This will involve discussing what may work best with the interviewee before the interview.

- Make plans for creating the right environment that supports reflective thinking, e.g., for some people this may be outdoors, or whilst they engage in a craft. For others, it will be in a quiet space at home. Again, this will involve discussing what may work best with the interviewee before the interview.

- Discuss whether they would like someone else to be present during the interview (i.e. a care partner). Along with providing comfort to the person with dementia, this might also help inform or trigger their responses. If the other person does engage in the interview, be mindful of whether the person with dementia is still encouraged and supported to share their voice (e.g. using inclusive communication strategies).

- Prepare to share theory in the form of if-then propositions rather than full C-M-Os. Breaking down ideas within C-M-Os into bite-sized chunks, and linking them to actual events that are relatable for the person with dementia, may help them to engage in process-style thinking. If appropriate, give participants a list of proposed theories in advance of the interview to review, with an explanation of the purpose of the interview.

- Prepare tools to help support the teacher-learner cycle and process thinking during the interview e.g. vignettes and visual resources to support comprehension.

Vignettes, for example, could be helpful in demonstrating a situation and prompting personal reflections. Insights from social network mapping could help identify relationships that are relevant to mechanisms.

- Think through what language may support the interviewee to understand the purpose and meaning of your questions.

- Consider how other data, from accessible questionnaires, for example, could be used to inform the interview, and potentially address inconsistencies and gaps in interview data.

- Be prepared that for some, multiple shorter interviews (if practical) may be preferred.

During the interview

- Be clear about the purpose of the interview at the start. It could be helpful to inform the interviewee that there will be some probing or clarifying questions to try and fully understand why things happened (i.e. retroductive questioning). This might help reassure that this is part of the interview process, and not as a signal that they are giving the ‘wrong’ answers.

- Be reflexive in balancing theory engagement with supporting the interviewee’s right to express themself as they choose.

- Remain open to just focusing on one aspect of a realist programme theory (rather than many aspects of it) that people with dementia are more able/comfortable to engage with.

- Use moments in personal stories to introduce realist theory questions and draw out causal insights e.g. ‘how did that make you feel?’, ‘have things changed since X has become involved in your care’…..’what do you think X did that led to those changes’?

After the interview

- Take time to review the data afterwards, even when you think a realist interview may not have gone so well, you will often find an important nugget of insight.

- Provide an opportunity for the interviewee to share further insights.

How could future research further support the inclusion and engagement of people with dementia in realist interview?

- Analysis of existing data sets of realist interviews with people with dementia could help identify communication practices that support/hinder engagement. Findings could inform co-developed guidance.

- Studies exploring the use of technologies to help people living with dementia to engage in realist interviews, could help identify means for reducing the cognitive burden that realist interviews can create. For example, technologies could support temporal orientation and/or to provide ‘cues’ that nudge retrieval of memories that are personal to the individual (i.e. episodic memories). When a realist interview takes place shortly after an intervention, the person might be fatigued. Such technologies might help.

During the symposium, we also discussed how we could further support people with dementia to engage in realist programme theory development (though a Public and Patient involvement and Engagement/stakeholder role), throughout the various phases of an evaluation. We also agreed that training and support for the researcher was crucial. There are plans in motion that will enable action on ideas shared, which we hope to share in due course!

What further methodological discussions do we need to have?

- How the application of judgemental rationality (“making judgements and decisions about competing or contested epistemic accounts of reality, and developing the tools and criteria to do so, to arrive at plausible and accurate accounts of phenomena”),* could be used to help interpret data/infer evidence collected from people with dementia, who may experience distorted realities due to brain changes.

- How dementia may be affecting an individual (e.g. changes in the brain that distort memories) and to be aware that any disturbance these changes create might also be interacting with an intervention itself. This needs to be borne in mind in relation to programme theories, since distortion of memories might be a factor involved in triggering certain mechanisms and ultimately in the outcomes realised.

Visual illustration of RAID-ER symposium discussions by Dr Lisa Burrows

Literature that informed the blog

- Dalkin, S.M., Greenhalgh, J., Jones, D. et al. What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implementation Sci 10, 49 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0237x

- de Souza Silva MA, Huston JP, Wang AL, Petri D, Chao OY. Evidence for a Specific Integrative Mechanism for Episodic Memory Mediated by AMPA/kainate Receptors in a Circuit Involving Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Hippocampal CA3 Region. Cereb Cortex. 2016 Jul;26(7):3000-9. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv112.

- Manzano, A. (2016). The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation, 22(3), 342-360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389016638615

- Pawson, R., and N. Tilley. 2004. Realistic Evaluation. London: British Cabinet Office

- *Quraishi, M., Irfan, L., Schneuwly Purdie, M., & Wilkinson, M. L. N. (2021). Doing ‘judgemental rationality’ in empirical research: the importance of depth-reflexivity when researching in prison. Journal of Critical Realism, 21(1), 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1992735

- Rybczynska-Bunt, S., Weston, L., Byng, R., Stirzaker, A., Lennox, C., Pearson, M., Brand, S., Maguire, M., Durcan, G., Graham, J., Leonard, S., Shaw, J., Kirkpatrick, T., Owens, C., & Quinn, C. (2021). Clarifying realist analytic and interdisciplinary consensus processes in a complex health intervention: A worked example of Judgemental Rationality in action. Evaluation, 27(4), 473-491. https://doi.org/10.1177/13563890211037699

- The RAMESES project outputs https://www.ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_Context.pdf https://ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_What_is_a_mechanism.pdf https://www.ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_Realist_interviewing.pdf.